If you look on Upwork for eBook ghostwriting gigs, you’re going to see a lot of low-paying jobs. A lot of people are looking to pay a measly $100 for a small book of about 10,000–20,000 words ($80 to you after Upwork fees). These gigs are posted by wantrepreneurs with small pockets. Most of them are merely following the plans from some fifty-dollar online course about self-publishing, the kind that’s marketed with fantastic lines like, “Make $1000 a month while you sleep!” If you’re like most young Americans looking to pay the bills, getting paid $80 for a book is nothing when you consider the length. Any decent book will take at least a day and a half’s worth of work. You might be wondering, then: Who in their right mind would take on a gig like this? This is one nasty way that indie publishers exploit writers.

I don’t want to name names, but one KDP publisher I worked with (let’s call him Ozzie) published a YouTube video talking about why he prefers to hire writers with a ‘passion over profit’ mindset. The first reason he mentioned was that he could pay them less, though he did recover and say that he ends up paying them more.

I was rather disappointed in Ozzie’s business philosophy because I’d originally liked him on account of his earnestness and approachability. But Ozzie is in effect saying that he’d rather hire a writer who would be willing to do more work for less pay just because of their personal passion. In other words, his ideal writer would have no business sense.

The truth is that any writer who is charging money for their services should be concerned with dollars and cents. After all, the publisher purchasing your work and intellectual property is concerned with profits too. Rest assured that they aren’t doing this out of the goodness of their hearts for free. Their prerogative isn’t to participate in the gift economy like many artists. No, their goal is to, well, make art make money.

Because it’s all about business, the exploitative small businessperson tries to lower his or her costs (and risks) by finding “passionate” writers, thinking that people who are passionate about a particular niche will ask for less money to write something about that topic. It’s a reasonably effective recruitment tactic, and it’s one that I’ve seen used quite effectively throughout my career, both in the for-profit and non-profit sectors. Of course, I find it to be a rather distasteful and exploitative way to do business.

Write for passion and profit

I abide by my own business philosophy that’s informed by the exalted Toyota Corporation. During the first phase of my hiatus from traditional employment, I did a lot of business reading and learned a wealth about management, leadership, and entrepreneurship. One of the most impactful books I read was The Toyota Way, and one key concept that I took away is “yet” thinking. Rather than constraining themselves to designing a car that’s either luxurious or affordable, Toyota sought to create a car that’s luxurious yet affordable—thus creating the Lexus series. In the same way, why not hire writers who have both passion and a desire for profit?

There are a few possible reasons that these small Kindlepreneurs don’t want to hire writers who have good business sense. The first reason I can think of is that they have small pockets and are barely eking out any profit for themselves. A business-savvy writer would eat into their tiny profits. A second reason is that, if they really are making a good buck off your work, they wouldn’t want to share it with you. It’s one reason why these Kindlepreneurs keep you in the dark as much as possible. They don’t tell you anything about the book, including when it’s being published, the title it’s published under, the sales performance of the book, or anything else about it for that matter. The writer can use all of this information as leverage in negotiations.

How to Get Top Dollar for Your Writing

Anyway, whichever way you slice the cake, the bare truth is that writing for passion should never interfere with the profits that your passion can bring. Passion belongs in the personal realm. Profits belong in the business realm. The two should never be confused. If you’re writing something that will profit someone else, the dollars and cents you get for it should matter to you just as much as the characters in your book.

My recommendation to writers looking to be a ghostwriter is to take a hard look at the KDP ghostwriting gig. Most of the time, you’ll be expected to come up with the entire book itself—the idea, the outline, the actual writing. A quality book will rarely ever take less than a day’s work, especially if you’re just getting started. The value of your creativity should never be underestimated.

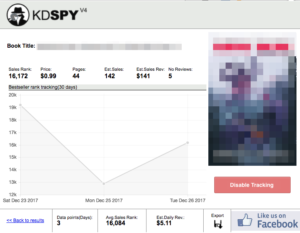

Now, to be clear, it’s perfectly okay to generate an idea and sell it off for cash. But make a plan on how to maximize the money you’ll get from that idea. In the fiction realm, there’s nearly always room for a series. So build that assumption into your narrative structure. When you write the first book in a series, make sure you end it with a cliffhanger. Then, keep a close eye on the performance of your book. I use KindleSpy (KDSpy), a Google Chrome browser extension that lets you track the estimated daily revenue of any Kindle book. For instance, one book I wrote is making an estimated $5 a day (though to be fair the data isn’t necessarily the most reliable on account of the fact that I haven’t tracked it consistently, and the book hasn’t been out for long enough).

How to Negotiate for More Money

I can use this information to negotiate with the publisher for a higher rate. At $5 a day and a 90-day break-even period, I can justify asking for $350 to $400 for the next book, which will sell for more than the first one. I also have leverage because I’m the one who created the intellectual property—having a different writer take over the series runs the risk of a reduction in quality in both the content and the writing. If you speak in the language of risk and reward in a negotiation, you stand to stack the odds in your favor. After all, if you’ve produced a book that does that sold fairly well, would your publisher want to risk switching to some unknown writer? The hand-off has the above risks, and hiring a proven writer will cost more. So long as you don’t ask for more than a more established writer, you ought to be in a good position to get what you ask for.

What’s Fair is Fair

Passion doesn’t put food on the table. Money does. You can’t put a price on passion, so the price should be based on the market value of what the publisher is trying to sell. Writers should be fairly compensated for the work that they do for publishers. After all, writers play a crucial role in turning a profit for them. So don’t let yourself be exploited. Passion will feed into the quality of your writing, and that translates to more profit. After all, quality work outlasts the competition, meaning your work will continue to sell well down the line (what KDP publishers call ‘evergreen’ content). And when a new book in a series does well, it boosts sales of the older books too.

I urge all writers to negotiate for more money. The more creation you have to do, the more you should be compensated. Set up a plan for yourself so that even if you don’t get a good deal on the first book, there’s room to get a better deal in subsequent books. Whatever the situation may be, always look for ways to increase your earnings as a writer. Don’t let publishers exploit you. Educate yourself about business and you’ll be glad that you can put food on the table as a writer.